Navigating Injury: The Art of Pacing and Progression

At Peninsula Osteopathy, we understand that injuries can be both physically and emotionally challenging. Whether you’re recovering from a strain, sprain, or a more serious injury, the journey to healing requires a thoughtful and strategic approach. In this blog, we delve into the importance of pacing activities and effectively progressing or regressing rehabilitation exercises, offering insights that can significantly enhance your recovery process.

Pacing: A Key to Successful Recovery

Pacing, often referred to as finding your “activity threshold,” is a fundamental principle in injury rehabilitation. It involves striking the right balance between engaging in activity and allowing your body the necessary rest it needs to heal. Here’s how to implement pacing:

- Listen to Your Body: The first step in effective pacing is tuning in to your body’s signals. If an activity causes pain, discomfort, or fatigue, it’s crucial to acknowledge these signals and adjust accordingly.

- Gradual Progress: The journey to recovery is not a sprint but a marathon. Start with gentle activities that don’t strain the injured area and gradually increase the duration and intensity as your body responds positively.

- Prevent Overexertion: Pushing yourself too hard too soon can lead to setbacks and potentially delay your healing process. Pacing helps prevent overexertion and promotes a gradual return to your usual activities.

- Build Confidence: Pacing allows you to build confidence in your body’s ability to heal and adapt. It also reduces the anxiety that can arise from the fear of re-injury.

Progressing and Regressing Exercises: Your Customised Approach

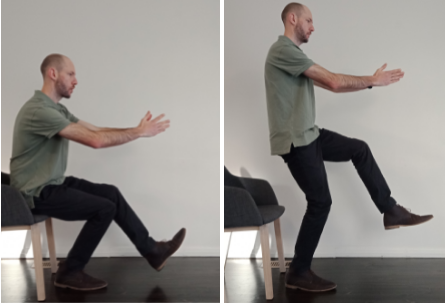

Progressing and regressing rehabilitation exercises play a pivotal role in your recovery journey. These strategies involve tailoring exercises to your current abilities while ensuring that you challenge your body within its limits. Here’s how to effectively utilise them:

Progression: As your body heals and gains strength, progression becomes essential:

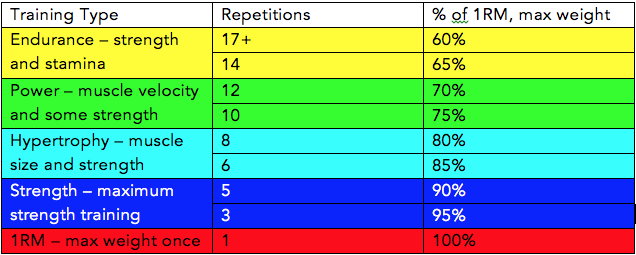

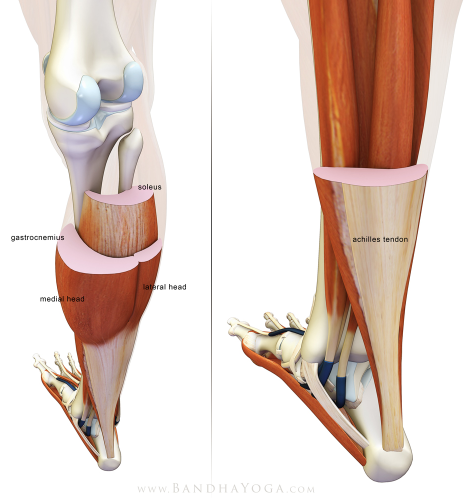

- Increase Intensity: Gradually add resistance or weights to your exercises. This stimulates muscle growth and strengthens the injured area.

- Expand Reps and Sets: Slowly increase the number of repetitions and sets to improve endurance and muscle conditioning.

- Embrace Complexity: Integrate more complex variations of exercises. This engages multiple muscle groups, enhancing overall strength.

Regression: There might be times when you need to take a step back to support your recovery:

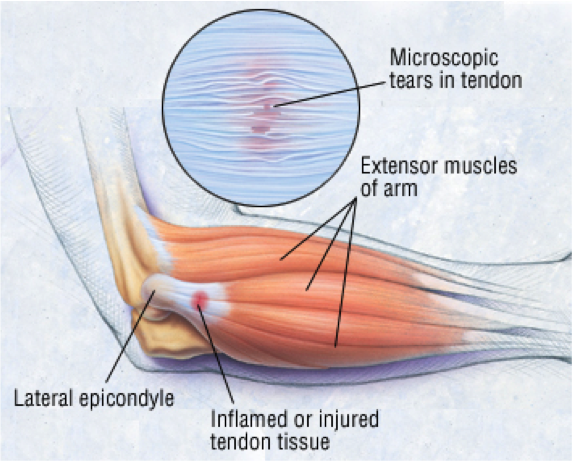

- Reduce Intensity: Lower the resistance or weight to prevent strain, especially if you experience discomfort.

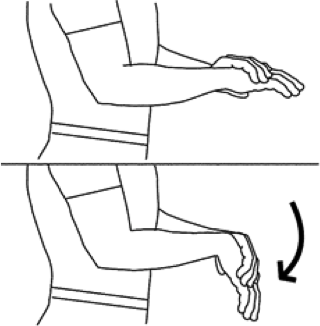

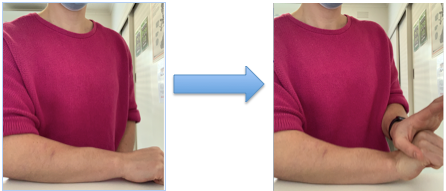

- Limit Range of Motion: If a movement causes pain, reduce the range of motion or opt for a modified version.

- Utilise Support: Incorporate assistive tools like bands or stability aids to provide support during exercises.

Musculoskeletal injury recovery is a process that demands patience, resilience, and expert guidance. At Peninsula Osteopathy, our expert practitioners are here to guide you through every step of your recovery journey. Pacing activities and skilfully adjusting exercise intensity are two powerful tools that can expedite your journey to healing. At Peninsula Osteopathy, we’re dedicated to providing you with the support and knowledge you need to make informed choices about your recovery. Remember, every step you take towards progress, no matter how small, is a step towards regaining your strength, mobility, and overall well-being.

Image: https://www.austinfitmagazine.com/March-2015/stay-in-shape-by-walking-with-friends/

Image: https://www.austinfitmagazine.com/March-2015/stay-in-shape-by-walking-with-friends/ Image: https://centerforliving.org/blog/5-best-self-care-tips-this-fall/

Image: https://centerforliving.org/blog/5-best-self-care-tips-this-fall/ Image: https://www.amhf.org.au/essa_helps_men_move_with_new_male_specific_exercise_resource

Image: https://www.amhf.org.au/essa_helps_men_move_with_new_male_specific_exercise_resource

Bent Knee Variation | Straight Leg Variation

Bent Knee Variation | Straight Leg Variation